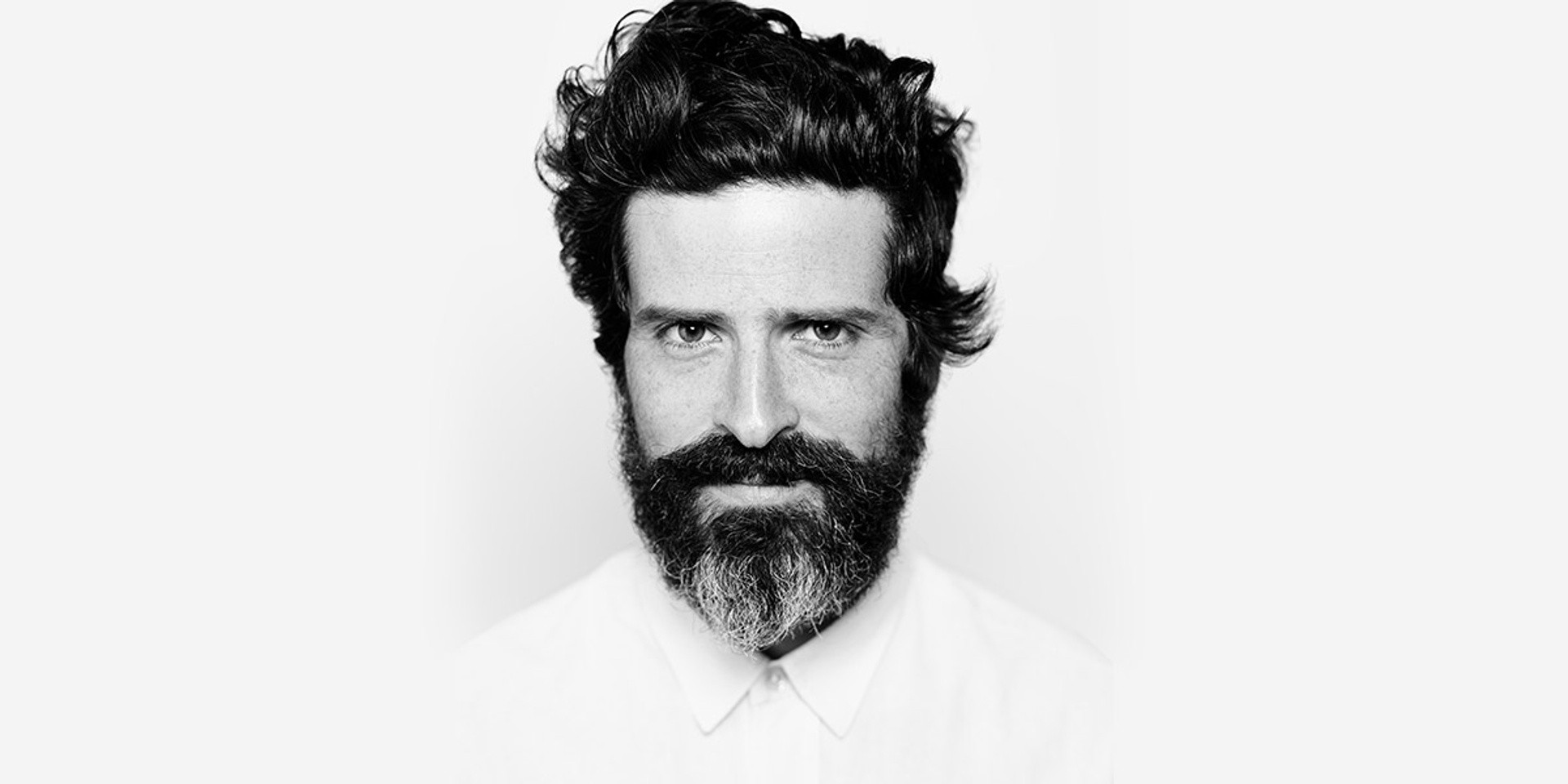

Whether he’s speaking or singing, Devendra Banhart sounds awed. His voice is the aural equivalent of a wide-eyed baby’s look of hushed amazement and mild bemusement. Its sui generis expressive power derives from that sonic quality and the generosity of spirit and empathy inherent in his natural register and utterance. And nowhere do both manifest more resplendently than on his recent album Ma.

“Folk”, in the broadest sense, has always been his most accessible and common veneer but on Ma, his shamanic singer-songwriter mode is concentrated with a focussed precision and magnified to encompass all the whispers and vibrations of the universe. Written for the child he may never or is yet to have, he has forged a work wherein every inch of space is blanketed by a palpable measure of love and warmth. All the better to live happily – and to take the blows that will come your way, with grace and humanity.

In the interview below, Banhart reveals some of the more crucial inner workings of Ma and expounds on its complex simplicity.

What would you say is the biggest difference between Ma and its predecessors?

There aren't any character songs. In all my records, there are at least four songs that are just characters, where I'm writing them from the perspective of somebody else. I love writing that way and that's kind of my thing. But this time, there aren't any characters; it's just me.

Also, the environment we were in – which is so pastoral, so natural, just basically redwood trees and the Pacific Ocean – kind of guided us into this more organic sound. In the past, if you had a string of ideas or just one idea, you just applied it to a synthesiser. I love that sound, it's also more convenient and a little bit cheaper, too. But this time, we had the real strings, real horns and a real piano. That felt quite different after some time of synthesising things.

You're an album artist. Between albums, what affects the kind of music you write the most?

My normal way of being is the opposite of what I'm doing right now, which is talking about anything, especially myself. My real job is to just go, get lost in the city or in nature, and listen. That's my process, in a way, and that's my normal state: Go disappear, try to observe and listen. The environment is the material for the album. And the environment for this album was being surrounded by all these kids. I grew up with these kids that are now adults who have kids!

My band are my friends and chosen family – we've all known each other since we were teenagers. Now, I see them and I can see them in this new light and relationship they have with their own children. And I am this aunty, which I've always wanted to be. I've got a lot of turtle necks, you know. So that became a big part of the record: This kind of maternal paternal relationship. For me, as somebody who doesn't have children, that relationship exists as something I can observe from a distance, and also exists between music and art where I have that relationship.

Between the primordial mothering elements, like the ocean and sun and moon, you can see mother everywhere. This seems like the real form of describing spiritual practice.

I feel like I have to ask you this: Have you never thought of having children of your own?

You know, the night is young. Buy me a drink and we'll see where this goes. No, I have. And I kind of feel like if if it happens, it happens. And if it doesn't, it doesn't.

Cate Le Bon and Vashti Bunyan are both part of the record. Why did you decide to work with them and what do you think they brought to the table?

I think they brought the best thing about the record. I'm so honoured they even agreed to do it. They're both so busy and they're way too skilled to be a part of this record. I'm shocked that they did that. Vashti, to me, embodies the archetype of the kind of wisdom of that music and art possess. She really is this incredibly powerful and wise person and the archetype of that kind of mothering quality. The record opens with a question and it ends with a question. And I wanted Vashti to sing on that last question, and she so graciously agreed. She's a dear friend and I love her so much that I didn't mind sending many annoying emails.

Same thing with Cate, who’s one of my best friends and somebody whom I play music with. Also, she had just made a record which I think is the record of the year and it's certainly my favourite record of the year, called Reward. She's touring behind it and I said, "Can you please sing on this record?” I don't know how she did it – it's very difficult to do anything when you're on tour other than just try to stay hydrated and play and get a little bit of sleep.

Something else that stands out about Ma is that though mourning, grief, and loss feature heavily, the overall sound is warm and intimate, even light-hearted in most tracks.

Well, it's just a part of our daily life, mourning and loss. It's just everyday: We're subconsciously, probably, or consciously mourning. And loss is certainly a big part of it. Maybe there's no need for mourning, but loss is definitely a big one. I think accepting loss comes with mourning. You can pretend you're not, like you can totally accept it– I mean, some people do, but I don't. I'm aware of so much loss and I mourn all of it. But also I accept it.

There are some very explicit songs on the record about losing people in my life and that process of mourning, but I think it's still an ongoing thing. Just like there's no shortage of suffering, there's no shortage of loss. That should just remind us to tell each other that we love each other while we can. And that's the most empowering thing I've discovered I could do.

Losing people that I love so much is telling the people that I can tell, who are still around, that I love them.

This is also the first time you've used one of your paintings as your album artwork. Why this album?

When the record was done, I just needed to find an appropriate image, and it felt like these flowers emerging from a void was the right image. I mostly draw, but that felt like a painting. So I decided to show paintings for the first time. Unfortunately, I'm not very good at them.

But it's beautiful. I love it.

Thank you, but you definitely need to go to the eye doctor after this.

This album features tracks of four different languages. Spanish (‘October 12’, ‘Abe Las Manos’) and English and Japanese (‘Kantori Ongaku’) and Portuguese (‘Carolina’).

That's all there is on earth. That's what they say. I think five or six, they've said, but really it's just four.

Do you see it as emotional code-switching or do you see them all as articulating the same truths?

Emotional code-switching, that's fabulous. I think it's fun to play with language and to slide in and out of certain languages but you really just do what's appropriate for the words, what's appropriate for the sentiment and what's appropriate for the song itself. So that's what really determines what the language is. I don't start off going, "I wanna do this in this language". What the song is about is what determines what language it's in.

I'm personally trying to get a hold of Weeping Gang Bliss Void Yab-Yum. It sounds like a Kurt Vonnegut book and he's one of my favourite writers of all time.

I love you for saying that. Breakfast of Champions… Actually, Slapstick is the funniest book I've ever read. I once wanted to get a tattoo of the butthole he does in Breakfast of Champions. Nobody makes me cry with a smile on my face like Kurt Vonnegut.

Does your poetry exist on the same continuum as your music, or is it something different entirely?

Poems are songs that don't have any music. When words don't have any music, they become poems.

You're involved with a bunch of different causes: The World Central Kitchen, I Love Venezuela and Rainbow Railroad. What has your involvement in these causes done to you emotionally?

It's the bare minimum, you know, I'm not doing that much. There's responsibility to some degree when people have this platform to talk about what's important to them. But at this moment, with social media in particular, and the fact that there's a charity for everything you care about. You can also, once in a while, just put a dollar into the thing that you care about whatever it is: Economic inequality, environmental degradation, orphanages, homelessness. There's no end to the stuff, and if there's a charity for that, you can just donate a dollar and it can make a huge difference. That's what my plan is, I'm lazy, but at least one dollar.

Like what you read? Show our writer some love!

-